Baseball great Ted Williams dies

By Rod Beaton

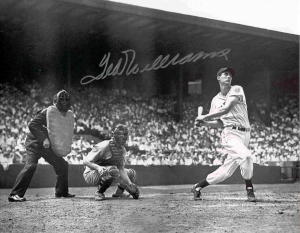

Ted Williams was the last major leaguer to hit .400 in a season.

Ted Williams — a sports and war hero and maybe baseball's

greatest hitter — died July 5 at age 83. A hospital spokeswoman

in Crystal River, Fla. said Williams was pronounced dead of

cardiac arrest. As a youngster, Williams dreamed of being known

as the greatest hitter ever, and many believed he lived that

dream. He was the last major leaguer to hit .400, reaching the

milestone in 1941 when he batted .406, and he captured six

American League batting crowns with the Boston Red Sox.

Williams was remembered at Fenway Park as groundskeepers began

shaving his No. 9 into the left-field spot where he used play.

The American flag in center field was lowered to half-staff hours

before the Red Sox entertained the Detroit Tigers.

At the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., a wreath was placed

around his plaque and a flower arrangement was put around his

statue.

In recent years, Williams battled a series of strokes and

congestive heart failure and got around in a wheelchair.

Williams' place in sports history — cemented long before — was

reinforced at the 1999 All-Star Game when he rode a cart from

center field to the Fenway Park infield and received an emotional

group hug from current baseball stars.

With San Diego's Tony Gwynn steadying him, a misty-eyed Williams

threw the first pitch to ex-Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk as the

crowd roared.

''Wasn't it great!'' Williams said later. ''It didn't surprise me

all that much because I know how these fans are here in Boston.

They love this game as much as any players and Boston's lucky to

have the faithful Red Sox fans. They're the best.''

Details of Williams' death

Williams was taken Friday to Citrus County Memorial Hospital

where he was pronounced dead of cardiac arrest at 8:49 a.m., said

hospital spokeswoman Rebecca Martin.

He had been bothered by health problems later in life, suffering

a series of strokes and congestive heart failure in recent years.

He underwent open-heart surgery in January 2001 and had a

pacemaker inserted in November 2000.

As a player, he combined power and batting average like no

others.

"He was absolutely the best hitter I ever saw," said no less of

an authority than Joe DiMaggio. And the Yankee Clipper's

sentiments were echoed by many, including fellow Hall of Famers

Bob Feller, Satchel Paige and Mickey Mantle.

''He is the premier measuring stick for all hitters,'' said Frank

Howard, who played for Williams in Washington from 1969 to 1971.

''The country lost a great American today.''

The death hit Hall of Fame shortstop and Williams contemporary

Phil Rizzuto hard. ''I am truly heartbroken, '' the Yankee great

said.

''When I was just a rookie in 1941, he took me under his wing,"

Rizzuto said. "After he hit a double one day, he called timeout

and told me, 'Kid, you've got a chance to play for the Yankees

for a long time, so bear down.' He was a credit to the game and

did so much for so many people.''

Williams' resume featured a .344 lifetime average, 521 home runs,

four home run titles, a record .483 career on-base percentage, a

slugging percentage of .634 that was topped only by Babe Ruth,

nine slugging crowns and a top-ten finish in runs per game with

.80.

Only the Babe walked more that Williams' 2,019 times, while the

Red Sox outfielder led the league in bases on balls eight times.

Williams' two Triple Crowns are matched only by Rogers Hornsby

and, if not for George Kell hitting .0000557 of a point better in

1949, he would have won a third.

Williams cracked his 521 home runs and recorded 2,654 hits

despite the loss of nearly five full seasons to military service

in World War II and Korea.

As a serviceman, his numbers were Hall of Fame.

He flew 39 combat missions in a Marine fighter in Korea and took

enemy fire three times.

Williams hit the big leagues as a 21-year-old in 1939 (.327, 31

home runs, a league-high 145 RBI) and hit .316 with 29 home runs

and 72 RBI in 1960, his final season.

In-between, he batted a celebrated .406 in 1941, .388 in 1957 at

39 and league-leading .328 a season after.

Until his death, he was no more willing to succumb to advancing

age than he was to give in to a pitcher with a good fastball. He

had the ultimate eye as his walk total shows.

Williams, doctors said, could see at 20 feet what people with

normal eyesight see from 10. Armed forces ophthalmologists said

his eyesight was so keen it was a one-in-100,000 proposition.

His swing was even more of a rarity. "I'd rather swing a bat than

do anything else," he said. The eye-and-swing combination was so

unerring he could actually tell if he hit a ball on the seams or

on the fat of the ball..

It was a self-taught swing, a left-handed stroke that had the

perfection of an architectural drawing and the speed and snap of

a horsewhip. Williams refined it on San Diego back lots and used

it to win a berth with the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast

League. He was 17 years old and stood 6-3 and 148 pounds.

Calling him skinny would be too kind. But calling him a tough

out, even then, would be no exaggeration. Hall-of-Famer Eddie

Collins noticed. He was scouting Bobby Doerr, a future Hall of

Famer, when Williams caught his eye. It was a golden moment in

baseball history, certainly the best thing that ever happened to

the Red Sox.

Williams filled out a bit and became a fixture in left field, the

devastating hitter of legend, the focus of an extraordinary

love-hate relationship with New England fans that was reflected

in his nicknames bestowed upon him.

Williams was singled out even in an era when the press handed out

freely colorful monikers. Many players had one nickname. Williams

drew four - "The Splendid Splinter," "The Thumper," "Teddy

Ballgame" and "The Kid" And to former teammate Johnny Pesky, he

was "No. 9."

Williams moved the best and the brightest in sports and

literature to rhapsody. No one expressed the special-man,

special-times essence of Williams any more John Updike, whose New

Yorker essay on Williams' final game, "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,"

has long been mandatory reading for baseball fans.

Updike, who sat in the stands that gray afternoon in September of

1960, lovingly detailed the last game, played before 10,454 at

Fenway Park, and how Williams shunned the standing ovation that

begged for one last look and a final bow.

"Gods do not answer letters," wrote Updike, maybe remembering the

photo of Red Sox fans carrying a banner calling Williams "God's

gift to baseball." Gods move in mysterious ways, their wonders to

perform. Few players had more mysterious ways and few performed

more wonders than Teddy Ballgame.

Perhaps a home divided by divorce contributed to his sometimes

sullen disposition. His mother was a Salvation Army worker, by

all accounts a zealot. His father ran a photography studio.

Williams cared little for fans, even less for sportswriters. He

favored the clubhouse men, cab drivers, in other words, the

underclass, people a step or two removed from needing the kind of

help his mother's work provided.

Williams was not one to shy from any confrontation. The opponent

could be a pitcher, a journalist or a North Korean fighter plane.

He did not pick his spots.

Doerr once compared Williams to Gen. George S. Patton. "No

retreat, no compromise." That included his reaction to the

Boudreau shift, an infield defense popularized by then-Cleveland

manager Lou Boudreau in which only the third baseman was on the

left field side of second base.

It is a strategy that Barry Bonds and Frank Howard saw in later

years — although never to such an exaggerated degree. Williams

might have bunted .500 if he had been inclined. He wasn't. No

retreat, no compromise and it wasn't until later in his career

that he began going more to the opposite field.

Williams also showed no compromise to his 1941 bid to become the

first .400 hitter since Bill Terry in 1930. Williams approached a

final-day doubleheader with a .39955 average. That rounded off to

.400 and meant he could have sat out. Williams would have none of

it and he proceeded to burn the Philadelphia A's for six hits in

two games for a .406 finish No retreat, no compromise.

"If there was a man born to hit .400," he wrote in his

autobiography, "it was me."

Williams' wartime service included time served with a future

astronaut, U.S. Senator and presidential aspirant John Glenn.

Williams was as cool facing life-or-death pressure as he was

facing anything a Feller fastball had to offer.

Glenn likes to tell of a mission in which Williams' jet was hit,

landed without landing gear, and Williams calmly got away from

his plane only moments before "it melted" on the landing strip.

Three years of play lost during World War II and almost two full

years in the Korean War denied Williams his chances at passing

Ruth's 714 home runs long before Hank Aaron shot by. As did many

who served from his generation, Williams had no regrets.

There were stormy times, to be sure. Mel Webb, a vindictive

writer, denied Williams a spot in his 10-man MVP ballot in 1947.

Williams batted .343 with 32 homers and 114 RBI that year, and

barely missed his second MVP because of Webb.

Williams spat contemptuously in the direction of the press box in

1956 after his 400th home run and once flung his bat that hit

then-Red Sox executive Joe Cronin's housekeeper.

Nine years after his 1960 retirement, Williams returned to the

game as manager of the Washington Senators. He stayed on for

three seasons in Washington and the club's first year as the

Texas Rangers. He won the '69 Manager-of-the-Year award, but that

was not his calling. He irritated plenty of people, but it is

because he irritated pitchers most — he often called them "the

dumbest people in the world" — that he was and is a baseball

icon. His death will never change that.

Between baseball, Williams became a Hall of Fame angler who

feasted on fish in Florida, Canada and many other places with

friends as varied as Stephen King, Bobby Knight and Curt Gowdy.

Williams also gave much of his time to the Jimmy Fund, a

Boston-based charity that fights cancer in children.

Politically, he befriended his old World War II buddy, George

Bush, and as recently as the winter of 2000 appeared at the

Manchester, N.H. baseball banquet with future president George W.

Bush.

Williams' fan base reached not only to the Boston laborer seated

in the bleachers, but also to non-New Englanders such as Kentucky

basketball coach Adolph Rupp and actor Robert Redford.

Williams made a sometimes overlooked diamond contribution during

his 1966 Hall of Fame acceptance speech when he urged inclusion

of Negro League stars in Cooperstown. Five years later, Satchel

Paige broke another version of the "color barrier" by receiving

baseball's ultimate honor and opening the door for other black

players.

Contributing: Bob Kimball, USATODAY.com, and wire reports

Baseball Articles

Baseball Drills